CMP and conditional branching

The use of a CMP instruction (CMPA, CMPB, CMPD, CMPX, CMPY, CMPU, CMPS) immediately followed by a conditional branch instruction (BCC, BNE, BHI, BHS etc) is sometimes straightforward to interpret, but not always.

For example, what does a CMP followed by a BCC ("branch on carry clear") mean? It actually means "branch if the operand is greater than the register value", though that's not necessarily clear unless you understand both how CMP works, and what the low-level implications of binary arithmetic are for the processor condition codes.

Let's start with an easier branching condition: CMPA and BNE ("branch if not equal"). The terms at least are straightforward; if the value in the register does not equal the operand, we branch. But let's look closer at how it works. Technically, the processor will branch here only when the Z (zero) condition code is set. This works fine because the CMPA has actually performed a subtract (again, not all that obvious from the op-code) and, although the operation discards the actual result of the subtraction, it does retain any condition codes that were set.

Suppose that we run these instructions:

LDA $C0

CMPA $1A

BNE ...

This performs a subtraction:

The result is not zero, so condition code Z is set to 0 and the BNE will branch. But if we were to perform these operations:

LDA $C0

CMPA $C0

BNE ...

We get a subtraction resulting in a zero:

This will set the Z flag to 1, and the BNE will not branch.

Knowing that the CMPA performs a subtraction allows us to similarly understand other branching operations like the BCC. Let's suppose we run these instructions:

LDA $C0

CMPA $1A

BCC ...

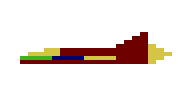

This performs this subtraction:

This is a positive number i.e. $C0 > $1A, so with our understanding that BCC is analagous to "branch if greater than", we perform the branch. However let's look at what's happening in the underlying binary to see how it actually works:

See what happens when you perform that calculation by hand, starting with the right-most digits and moving left. As with the subtraction of decimals, you have to borrow from digits to the right. To perform this particular subtraction we have to borrow from many of the minuend's digits, but the left-most digit does not require any borrows. The carry-flag, which also doubles as a "borrow" flag, is set to 0. Since the BCC operation will jump only when the carry-flag is cleared, we do indeed jump.

But suppose we were to compare a value where the minuend is less than the subtrahend:

LDA $C0

CMPA $DB

BCC ...

This leads to:

Take a look at that and realise that the answer is not really $E5, it's -$1B. Of course, since we're treating our 8-bit digit as an unsigned integer we can't actually represent a negative number, so we instead loop back to the maximum ($FF) and keep going. A side effect of doing this is, however, that the carry flag (or "borrow" flag) is set to 1.

Let's look at the binary to understand why:

In this case the left-most digit of the minuend also requires a borrow, but there are no more digits to borrow from. We "borrow" one anyway and set the carry flag. If this were the lower-byte of a larger number - for example, a 16-bit number - an SBC ("subtract with carry") allows the carry flag to be usefully employed to borrow from the upper byte minuend e.g. For example, take the calculation for:

With our 8-bit registers this needs to be performed in two separate subtractions:

LDD $39C0

SUBB $DB $C0 - $DB (sets carry)

SBCA $18 $39 - $18 (borrows from AND sets carry)

This performs two subtracts. The first is the same as we saw before, but in addition to calculating the result $E5, also sets the carry flag:

The second uses the carry flag, subtracting an additional 1 to ensure the correct result of $20:

When dealing only with 8-bit numbers, as we our with our CMPA and BCC, the carry flag merely acts as an indicator that the result was negative.